Volume II: Filmography

Volume II: Filmography Volume II: Filmography

Volume II: Filmography

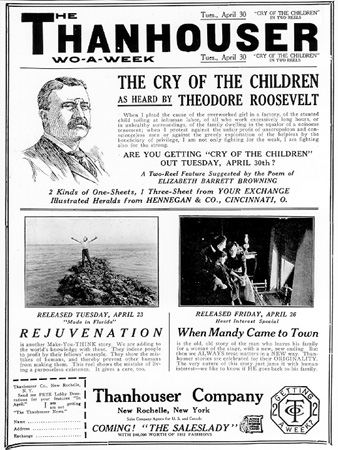

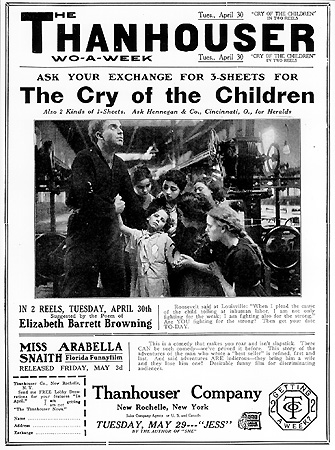

Advertisements from the Moving Picture World, April 6, 13, 20, and 27, 1912. (F-340, F-350, F-360, F-370)

April 30, 1912 (Tuesday)

Length: 2 reels

Character: Drama

Director: George O. Nichols

Scenario: Suggested by Elizabeth Barrett Browning's poem of the same title

Cameraman: Carl L. Gregory

Cast: Marie Eline (Alice, the little girl who dies), Ethel Wright (the working mother), James Cruze (the working father), Lila H. Chester (the factory owner's wife)

Notes: 1. Quotations from Elizabeth Barrett Browning's poem were used in the subtitles. 2. An Edison film released the month before, Children Who Labor, was also billed as having been based on Mrs. Browning's poem. The Edison production had the endorsement of the United States National Child Labor Committee.

BACKGROUND OF THE SCENARIO: The Cry of the Children was one of many poems written by Elizabeth Barrett Browning. Born Elizabeth Barrett in England in 1806, she was one of 12 children who grew up under a wealthy, tyrannical father. Educating herself for the most part, Elizabeth became well versed in classic literature and prosodic theory. With her family she changed addresses several times in England until 1845, when she met poet Robert Browning. The two married secretly in 1846 and moved to Italy, where Elizabeth took an active interest in politics. A prolific poet, her works were considered excellent in their day, even finer than her husband's output, but her political views offended many. Broad-minded and with an interest in society, she made the Browning couple regular company of the likes of Hawthorne and other writers. Her death occurred in 1861. The Cry of the Children was frequently quoted in England and America during the turn of the century crusade against the evils of child labor and was reprinted, among many other publications, in Pamphlet No. 66 issued by the Child Labor Committee in New York in 1908.

ARTICLE, The Moving Picture News, March 16, 1912:

"While the country is discussing the Lawrence (Massachusetts) strike and the removal or 'kidnapping' of the strikers' children, Thanhouser announces a timely feature in The Cry of the Children, after the poem by Elizabeth Barrett Browning. As a child-labor subject, the producers feel they have gotten together something that will live through the ages and work benefit through the ages. It is released Tuesday, April 30th, in two reels. It is in Thanhouser's 'Can Such Things Be?' series and with a strong line of paper will help put the picture show under the New York World's definition of 'civilizer.'"

ARTICLE by Gordon Trent, The Morning Telegraph, March 24, 1912:

"Some prominent New York students of sociology were permitted by the Thanhouser Company to visit their studio last week during the filming of the Elizabeth Barrett Browning poem, The Cry of the Children. This is considered by many the greatest child labor epic ever written. It is suggested that exhibitors showing this film make capital of it by inviting leading sociological students in their localities to see it, and getting it before the friends of social uplift generally. The picture is in two reels, released Tuesday, April 30, and because of its nature is expected to 'make a noise' in all parts of the country."

ARTICLE, The Moving Picture News, April 13, 1912:

"Independent booking exchanges report an unusual advance demand for The Cry of the Children, the Thanhouser child-labor feature, especially in sections where there are factories. The subject is said to deal as boldly with the child-labor problem as the original poem by Elizabeth Barrett Browning. Thanhouser announces that a real factory was converted into a film studio to give the film accurate 'local color.'"

ARTICLE by Gordon Trent, The Morning Telegraph, April 21, 1912:

"Bang! Bang! One after another, Thanhouser will give the Cry of the Children on Tuesday, April 30, and now they push over an announcement of Jess, by H. Rider Haggard, for Tuesday, May 28. Three sheets for Cry of the Children are going fast at the Independent exchanges, also the two varieties of one-sheets. Prices of booklets are supplied by Thanhouser Company on request. Exhibitors in their advertising are advised to use the words of Theodore Roosevelt on 'the cry of the children' to this effect: 'When I plead the cause of the overworked girl in a factory, of the stunted child toiling at inhuman labor, of all who work excessively long hours, or in unhealthy surroundings, of the family dwelling in the squalor of a noisome tenement; when I protest against the unfair profit of unscrupulous and conscienceless men or against the greedy exploitation of the helpless by the beneficiary of privilege I am not only fighting for the weak - I am fighting also for the strong.'" (Adapted from a Thanhouser news release)

SYNOPSIS, The Moving Picture News, April 20, 1912:

"PART ONE: 'Do you hear the children weeping, Oh my brothers, Ere the sorrow comes with years?' - asks Mrs. Elizabeth Barrett Browning in her wonderful poem, which is the denunciation of child labor that will never be forgotten. And in it she tells of one little girl who died and whose little fellow laborers accompanied her body to the grave. They did not weep, for they loved her, for, as the poem tells, their one thought was 'From the sleep wherein she lieth, none will wake her crying, 'get up little Alice, it is day.' Little Alice, more fortunate than some of the others, was not always a child slave. She was the youngest of three children, and the pet. Wages were small, but her parents and her brother and sister found it possible to feed an extra mouth, although the margin between income and expenses was pitifully scanty. So little Alice, for a time, was a happy child, not a tiny old woman as were the other little girls in the manufacturing town.

"The wife of the owner of the mill was a selfish, dissatisfied woman, who seemed to have everything but really had nothing. Driving out in her auto one day, she saw little Alice, and immediately was struck with the youth and beauty of the little child. A creature of impulse, she decided she wanted Alice for her own, and summoning the parents told them of the good fortune in store for them. Much to the rich woman's surprise, they did not see it as she did. They did not want to give up the child, and said so. The mother, however, thought of the advantages that Alice would have if she accepted the offer. With true self-sacrificing mother love, she told little Alice that she could go to the home where riches awaited her, but the decision rested entirely with her. The child looked from the 'pretty lady' to the homely, poorly dressed woman and the man, and the two tattered children awaited her decision with breathless interest. On the one side was a home, certainly with plenty of money and perhaps where love also could be found. Poverty was on the other side, poverty without hope, but she 'knew' that love was 'there' and could never be driven away. Her choice was made, she threw herself into her mother's arms. The 'pretty lady' watched the happy, shabby group through her lorgnette, then muttering 'it is useless to try to do anything for the poor,' she entered her auto and was driven back to her beautiful home, where love and self-sacrifice did not abide.

"PART TWO: Little Alice was an odd figure in the grimy town she called home, because, unlike the other children, she did not work in the mill. Her father, mother, brother and sister worked there many weary hours a day, and made many sacrifices so that 'baby Alice' might remain a child and did not become an old woman before she was in her teens. The wife of the rich miller had seen Alice, been struck by her appearance, and offered to adopt her, but although the parents were willing to give her up, for her own good, she delighted their hearts by declining to do so. Later, trouble came to the family, and to many others in the town. Wages in the mill were reduced, and the workers struck. It was a strike of desperation. The workers had no money, no helping hand was extended to them, and what the mill owner had predicted to them came to pass. They were starved out, and crept back to their old places at his terms, and were worse off then they had been before. The strike made a great change in the future of little Alice. Her mother was frail, and the period of semi-starvation through which she had passed, weakened her the more. She tried to go back to work, but was unable to do so. So little Alice insisted on being a wage-earner, and her parents could not forbid it, as the money was sadly needed, and every penny counted.

"In her new environment little Alice speedily lost her freshness and beauty, for as the poem says, 'Well may the children weep before you, they are weary as they run; they have never seen the sunshine nor the glory which is brighter than the sun.' So day by day the child faded away, becoming old and haggard before her time. The mother of Alice was also growing weaker, and the child knew that only money and rest could restore her. So her thoughts turned to the 'pretty lady' who wanted to adopt her, she decided for her mother's sake to accept the offer; but the 'pretty lady' scornfully turned her away, telling Alice she was old and ugly now, and that no one would want her. Also, she had a pet, a poodle dog, that held the chief place in her affections. Little Alice returned to the factory, and lived out her brief life there. She was stricken while at work, and died there. The other children did not grieve, they envied her, but the 'pretty lady' who met the mourners returning from the funeral, shuddered, and was serious and thoughtful for once in her butterfly life. Perhaps the last two lines of the poem described her feelings, 'For the child's sob in the silence, curses deeper. Than the strong man in his wrath.' This is the story of little Alice. Many believed it was fortunate for her that she died while a child in years, even though she was a woman in sorrow."

REVIEW, The Bioscope, October 10, 1912:

"We have always held that the most suitable literary form for the purposes of cinematograph adaptation is the poem. The poet is usually more of a word-painter than the prose-writer, and he depends less upon dialogue; his products are, therefore, peculiarly apt material for the maker of picture plays, who may visualize his word pictures into dramas for the screen with very little alteration of theme or arrangement. One of the latest 'materialized poems' is the Thanhouser Company's beautiful Cry of the Children, suggested by Mrs. Browning's famous work of the same name. In this case, of course, the film sets forth the idea of the original in the form of a play; it applies its sentiments to modern life, preserving its spirit, but clothing it in present-day dress. The result is so good that it would be difficult to praise it too highly. It has all the elements necessary for a popular success, and is, at the same time, a true work of art. Very cleverly has the play been pieced together from such indications of a story as are to be found in the poem, the 'Little Alice' of the latter being made the heroine of the former, and illustrations being given on the screen of such well-known passages as: 'The young lambs are bleating in the meadow, The young birds are chirping in the nest,' the inclusion of which in no way lessens the dramatic force of the story, and goes far towards rendering the whole adaptation complete.

"Of the moral significance of the film, it is, perhaps, unnecessary to speak, since Mrs. Browning's poem has been to the particular evil it deals with what Uncle Tom's Cabin was to the slavery question. And it can truthfully be said that the lesson gains in force, if that is possible, by visualization. The finish of the picture is particularly striking. Instead of spoiling the whole force of the argument, as so many producers have done in similar works, by insisting on the conventional, unreal 'happy ending,' and thereby effacing whatever impression may have been made, they have rung down the curtain on a grim tableau of misery and of great wrongs still unrighted, leaving the spectator roused to a realization of the tragedies which are actually happening, and which are waiting for remedy, not soothing him down with a plausible lie that reparation has been made, and that all is now as it should be.

"Thanhouser's Cry of the Children preaches one of the strongest sermons that have ever been delivered from a screen. There is no mawkishness about it, nor undue sentimentality. it is plain for all to see, and it vibrates with a stern truthfulness that is not to be avoided. The acting of the film is on a level with its conception and general production. The cleverest kiddie gives a very telling performance as 'little Alice,' whilst another wonderfully-finished character-study is that of the butterfly - woman, the mill-owner's wife, who is simply incapable of understanding the sorrows which surround her, because she has never known them herself. It seems a pity that the producer, otherwise so consistently artistic, should have thought it necessary to affix a trademark 'sticker' to the wall in one of the scenes. It is only a small point, but it is not a laudable practice. The staging of the film throughout is admirable, and some of the factory scenes, both interior and exterior, quite especially remarkable. Altogether it is not too much to say that The Cry of the Children is a masterpiece of the cinematographer's art, entirely worthy of the source which inspired it. It is a film which ought to be shown everywhere."

REVIEW, The Morning Telegraph, May 5, 1912:

"Elizabeth Barrett Browning's poem of the above title is presented in photoplay form by the Thanhouser Company in such an entirely praiseworthy way that it is difficult to speak of it and not overreach oneself in expression of the word. In two reels, none too many or long, it is dramatic, powerful in its depiction of the child-labor evil as prevalent in the mills and factories of the land, and thoroughly consistent in its evolution of the play. It would be difficult to imagine any production more real than is this, the actual scenes of whirring machines guided by the hands of the grown folk and the little ones, the out-of-door pictures of the crowds of workers going to and from their labors, the sharp comparison between the home of the mill owner and the poor workman, whose family are obliged to toil with him; the characteristic self-regard of the rich wife, pampered to the point of ridicule until the craving for child-love is easily satisfied in the petting of a puppy; each and every phase and angle of modern-day social contrast makes the photo-play distinct and dramatic to a degree.

"All save the littlest tot of the poor man's family are forced to work in the mills and she alone is saved through the sacrifice of the others. In her comprehension of the desire of the rich woman to adopt her, though the request had been refused by her parents, the child later on, worn by baby worries and lack of sustenance, offers herself, that her own folk may live, going in the night to the home of the rich, to be rejected with scorn and decision, her beauty and joy gone from her face. Then she, too, is sacrificed to the mills and her little life is ground out in the toils, to be at last laid away for its final resting in the poor little grave without its headstone. Then do the rich man and his wife realize the crime they have committed, and the finale shows the realization as the visions of what their selfishness has caused is brought back to them when it is too late. It is acted splendidly by each and every player, and it should be seen by all workers in mill, office, shop or elsewhere, for it awakens a realization of conditions as they are."

REVIEW, The Moving Picture World, May 11, 1912:

"The Moving Picture World has already commended this glorious, two-reel feature made after the poem of Elizabeth Barrett Browning, and has pointed out the value of such releases to humanity and their civilizing power. This reviewer, however, takes pleasure in pointing the charm of the picture that most strongly appeals to him. It is in the character of the mill worker's youngest child, a vivid and quite fresh creation. The producer, in the way he has handled the possibilities that this character gave to him, shows a sensitive, poetic imagination. This child, played by the Thanhouser Kid, seems the very breath of poetry, and, to give one instance, that scene in which we see her beside the bunch of pussywillows, changes the effect of every other scene in the picture. The picture needed some such contrast in order to bring out its values at all, but this, coming as it does with the scene just before, shoots like a poignant cry to the very last scene. We wish that all the contrasts offered by the picture were as sincere. These scenes really live. The picture, as a whole, has much living truth and is very effective. The camera work is good."

REVIEW, The New York Dramatic Mirror, May 8, 1912:

"The cruelty and injustice of the great evil, child labor, are vividly reflected in this polemic. The directors have wisely made no attempt at an intricate and ineffective plot, but have employed a simpler more direct method, that of relating without complications the story of the struggle for existence in a mill worker's home. The story opens with a scene in the mill worker's home - a typical one, no doubt. It is dawn, and the children are reluctantly dragging themselves out of bed, preparatory to going to work in the mills. They greet the new day with no smiles of gladness, but with sighs. Little Alice, the six-year-old sunbeam of the household, is the only one who relishes life, and she is still unstained by the sordidness of the mills. After the departure of the others to the mills, the little tot chances to scamper into a nearby field, where she is observed by the mill owner's wife as she swirls by in her car. The child's joyousness and the vivacity captivate the childless wife, and upon the following day she ascertains were Alice lives and pleads with her parents to allow her to adopt the child for her own. The parents courteously but firmly refuse to part with their sunbeam, and the wealthy wife leaves in a huff.

"Two months later, when a tedious strike has left the family in insufferable privation, little Alice is compelled to go to the mills to take her place alongside of her brothers and sisters. So great is their misery, though, that to lighten the load, Alice bravely volunteers to give herself up to the mill owner's wife, who only a short time before had been entranced by her beauty - a beauty, which now, has been blighted by the incessant toil and brutal treatment. The child's visit to the wealthy woman is all in vain, and she returns to the mills to resume the body-wracking, spirit-crushing labor. The wife does not wish for a child whose face bears the scars of poverty and exhaustion, for which her husband's sister of labor is directly responsible. Little by little Alice's strength ebbs; her cheeks grow paler; her body becomes emaciated, and her smile much fainter. The inevitable will come, and on one particularly wearisome day she collapses at her machine, swoons to the floor, and before anyone can reach her, dies of exhaustion. The mill owner's wife, who chances to be at the office that afternoon, sees the stricken parents bear the form of their dead child out of the shop and across the fields to their hovel, and to her credit, bursts into tears. Later, an opportunity is placed in path to observe the simple little funeral of the child, and the pitifulness and wrong of it all so impress her that she attempts to make her husband see the question in the light which she sees it. Her pleas strike no responsive chord in the husband's nature, though, for he is calloused to argument and inured to stories of suffering. While with bowed head the wife stands at one window of their home, Alice appears to be to her transfigured; and simultaneously at another window the husband with a perplexed frown gazes steadfastly into the street below, his vision of stacks and whirring machinery fades and melts before his eyes. The play is tremendously impressive, and although it suggests no solution to this vital problem, leaves in the spectator's mind the realization that the conditions depicted are not at all myths of the past but facts of the present. The acting throughout is excellent, while in the selection of the scenic backgrounds the greatest care has been exercised. The picture is in two reels."

# # #

Copyright © 1995 Q. David Bowers. All Rights Reserved.