Volume I: Narrative History

Volume I: Narrative History Volume I: Narrative History

Volume I: Narrative History

When Edwin Thanhouser started making films in 1909 the industry in America was scarcely 15 years old. For much of that time Edison, Lubin, Vitagraph, American Biograph Note and others produced pictures of "filler" quality. One of American Biograph's main activities was filming boxing matches, races, and other "action" events for peep-show devices called Mutoscopes. Until about the 1907-1909 period, very little was done in the way of producing pictures with serious dramatic content. "If it moves, let's film it," seemed to be the credo of most manufacturers. This was just fine with audiences, who were entertained by the novelty value of the medium.

Mutoscope

The formation of the motion picture industry in America can be traced to Thomas A. Edison, who in 1888 enlisted the assistance of William Kennedy Laurie Dickson, a new employee, to develop a device for recording photographic images in rapid sequence. Note Named the Kinetograph, the machine underwent further development and refinement, and by 1890, in combination with an Edison device known as the Kinetoscope, images could be recorded on film, and viewed with the accompaniment of sound from an Edison cylinder phonograph. Some of the earliest motion pictures were thus "talkies." Note

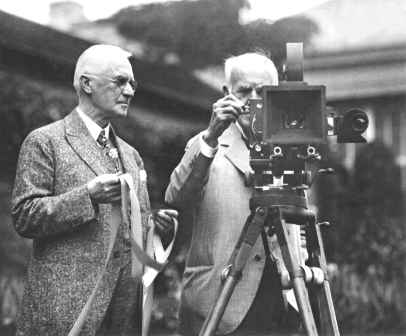

Thomas Edison (L) and George Eastman (R)

In 1892 the Kinetoscope was made in the form of a nickel-operated peep show, however it was not until early 1894 that units were installed in commercial locations. In the meantime, at the World's Columbian Exposition, held in Chicago in 1893, the Anschütz Tachyscope, a coin-operated device which featured a circular glass plate revolving within a cabinet, with pictures on the outer rim of the disc appearing in succession as a light flashed, attracted attention. While the Tachyscope proved to be ephemeral, the Kinetoscope caught on with the public, and by the end of 1894 Kinetoscope parlors were operating in major cities in the United States and several foreign countries as well.

In the meantime, Edison's development of a machine to project images on a screen in a theatre was encountering difficulties, so in 1896 he purchased the rights to Thomas Armat's Vitascope projector, eventually marketing it under the Edison name. Soon thereafter, the Vitascope mechanism was discontinued, and a new device, the Projecting Kinetoscope, made its appearance. However, the Vitascope was to play an important part in the history of the motion picture in America, for one of these devices was used on April 23, 1896 at Koster & Bial's music hall in New York City to project pictures on a screen for a paying audience, the first time this had been done on a large scale in the United States. Note The first person to show films to small audiences of paying patrons will probably never be identified with certainty, as there were a number of claimants who stated they did this in America prior to April 1896.

The year before, on December 28, 1895, Louis and Auguste Lumière, known as the Lumière brothers, projected films on their Cinématographe to Frenchmen who paid a franc apiece to gather before a screen in the basement of the Grand Café in Paris. Films used in these and other early performances were short subjects lasting only a minute or two, or even less, and featured acrobats, dancers, vaudeville skits, trains, and other topics emphasizing rapid motion.

In the beginning, films were used as short fillers between vaudeville acts and plays and as carnival and amusement park attractions. By the turn of the century, virtually every vaudeville theatre in America had exhibited motion pictures as a part of a larger program. Although various "Vitascope parlors" and other storefront theatres had been set up by the turn of the century expressly for the showing of movies (as they came to be popularly called), it is evident that until about 1905 the vast majority of motion pictures were projected in connection with stage performances or other entertainment in theatres, opera houses, and other locations built for stage work.

The subjects covered by films of the early 20th century included political campaigns, boxing matches and other athletic contests, visits to Coney Island and other amusement parks, the arrival of warships in port, military activities (the Spanish-American War of 1898 provided opportunities in this regard), races, trains in motion, animals, dancers and acrobats, and scenery - in other words, subjects not much different from those used at the inception of films projected to paying audiences in the mid-1890s. By 1903, thousands of different short subjects from various American and foreign studios had been shown on this side of the Atlantic.

While a number of films could be cited for their technical importance or popularity during the early years, one of the most notable was The Great Train Robbery made by Edwin S. Porter for Edison and released in 1903. This subject, which featured excellent dramatic content, lots of action, and good photographic quality and editing, was widely cited in later years, and by 1915 had become recognized by historians as a pioneering classic. Porter also produced The Life of an American Fireman and a version of Uncle Tom's Cabin. In the early days, films imported from Georges Méliès, Pathé Frères, and others were popular, with Méliès' 1902 Trip to the Moon being especially so. Still, most films of the first few years of the 20th century were short, of an impromptu and unrehearsed nature and, in the absence of meaningful plots or dramatic content, depended upon motion effects or scenery for their entertainment value.

Although the vast majority of American subjects produced before 1910 were of one-reel (approximately 1,000 feet) length or less - far less in the early years - there were some notable exceptions. On March 17, 1897 in Carson City, Nevada, Enoch J. Rector exposed 11,000 feet of film to record the Corbett-Fitzsimmons boxing title bout, releasing it as a feature 90 minutes in length which he projected on his Veriscope device to paying audiences. In 1898 the American Mutoscope & Biograph Company released a 5,575-foot film of the Jeffries-Sharkey boxing match filmed at Coney Island, and Vitagraph issued a lengthy version of the same contest.

During the period from about 1905 to 1908, films were typically sold for 12 cents per foot, calculated in precise amounts. For example, in 1907 Pathé offered a 967-foot version of Cinderella, priced at 12 cents per foot, for a total of $124.04. Such films were typically bought by exchanges, but some exhibitors, especially those with multiple theatres, were buyers as well. In addition, certain classics were often bought by the owners of small theatres, who would rerun them frequently.

In 1909-1910 Vitagraph produced Les Misérables and The Life of Moses in four and five reels respectively, but distribution practices through exchanges at the time mandated that each feature be parceled out at the rate of one reel per week. In addition, film manufacturers of the era were content with the profits derived from one-reelers, and there was little inclination at the time to invest additional capital and to hire individuals sophisticated enough to create multiple-reel productions. When D.W. Griffith produced His Trust in two reels for Biograph in 1910, it was split apart into two films, one titled His Trust and the other designated His Trust Fulfilled. Similarly, the 1911 Biograph two-reel production of Enoch Arden was released on two separate dates as part one and part two. Numerous other examples could be cited.

In the beginning, motion picture production in America was centered in New York City and neighboring Northern New Jersey, with Fort Lee, New Jersey soon developing into a major area with several studios. Not far away, in Philadelphia, Siegmund Lubin was building a film empire. The numerous legitimate and vaudeville theatres in the greater New York area provided opportunities to hire actors and actresses, most of whom were eager to earn the usual three to five dollars for a day's work as an "extra" in films. The Eastern production companies such as Biograph, Nestor, Lubin, Vitagraph, and others sent companies of players to California during the winter months to exploit the advantages offered by warm weather, bright sun, and longer daylight hours, plus certain types of scenery not available in the East, such as snow-capped mountains and sandy deserts. By 1910 several production companies were located full-time on the West Coast, and by 1915, Los Angeles and the surrounding area constituted a major film center. However, in 1909 when Edwin Thanhouser made his start in the industry, Los Angeles was just beginning to be recognized for its moviemaking potential.

Copyright © 1995 Q. David Bowers. All Rights Reserved.