Volume I: Narrative History

Volume I: Narrative History Volume I: Narrative History

Volume I: Narrative History

Entering the business was no easy matter for Edwin Thanhouser or anyone else in 1909. America was a free country, but that freedom did not exist in the field of motion picture production. For a number of years the industry had been the private preserve of American Biograph, Edison, Vitagraph, Selig, Lubin, and a handful of other pioneers. Seeking to exclude others from entering what was becoming a growing and profitable business arena, the leading companies buried their differences and combined into the Motion Picture Patents Company, which was incorporated on September 9, 1908 and announced to the trade on December 18 of the same year. Note

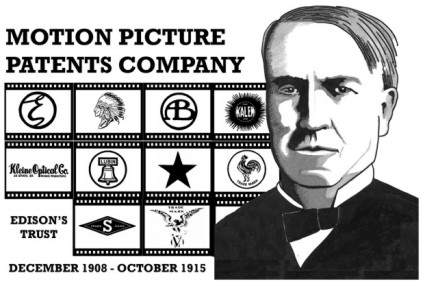

Members of the combine referred to as the "Trust" or "Patents Company" were designated as "Licensed" companies, as opposed to those excluded from the cartel, who became known as "Independents." Making up the Patents Company in 1908 were the founding members, consisting of the American Mutoscope & Biograph Company, the Edison Manufacturing Company, the Essanay Film Manufacturing Company, the Kalem Company, George Kleine (a film importer), the Lubin Manufacturing Company, Pathé Frères, the Selig Polyscope Company, and the Vitagraph Company of America. In 1909 the Gaumont Company and Gaston Méliès were admitted to the group. Previously competitors, and often litigants against each other, the firms comprising the Patents Company were strange bedfellows, and the alliance was strictly one of greed, not one of camaraderie or mutual support.

Thomas Edison with member logos of the Motion Picture Patents Company (aka MPPC or The Trust)

At the outset, the Trust sold licenses to local and regional film exchanges, which purchased or leased footage from the various manufacturers and rented or sold it to individual theatres. In April 1910, a few weeks after the Thanhouser Company had its first release, the General Film Company was set up by the Trust to purchase exchanges and to secure a tighter grip on the industry. Eventually, 57 exchanges were acquired, and the licenses of 10 other exchanges were cancelled. Under various agreements many theatres were persuaded to handle only Patents Company films, for which a license fee of $2 per week (later increased to $5) was paid, in addition to a royalty of 12 cents per foot of film. The exchanges in turn paid the individual film makers who comprised the Patents Company a royalty of 10 cents per foot.

Before 1902 when the exchange system began, individual exhibitors purchased or rented films directly from Edison, Vitagraph, and other makers as well as middlemen who imported footage from makers in France and elsewhere. With little in the way of quality control in the industry, many theatres were forced to exhibit poorly patched, stained, and otherwise damaged films. Early exchanges sought to provide a wide variety of films and services. Dirty films were cleaned, damaged films were repaired, and "rainy," burned, and incomplete films were retired from circulation. By dealing with an exchange, an exhibitor had a choice of hundreds of titles, including new releases. Soon the exchange system became pervasive in America, and by 1910 no large city was without one or several.

Exchanges affiliated with the Patents Company maintained a firm grip on prices, but Independent exchanges were flexible and charged varying rates to exhibitors, usually nine to 12 cents per foot, or less, especially for older subjects, foreign imports, and products of obscure makers. Many side deals were made, and certain Patents Company firms would undercut each other or make unauthorized copies (a process called "duping") of another's films if they thought they could do so without detection or reprisal. Other problems arose with the continued use of worn, poorly patched, or stained films, and with dishonest bookkeeping.

The Patents Company owned or controlled camera, projector, and other patents secured or invented by Thomas Edison, American Biograph, Thomas Armat, C. Francis Jenkins, and others, and, as if this were not enough, it had an arrangement with Eastman whereby only Trust members could use Eastman film. Seeking to prevent anyone else from gaining a foothold in the business of motion picture production, the Patents Company was said to have hired thugs to smash the cameras of anyone using stray Edison, Pathé, or other designated machines. Note Any suspicion that a newcomer was using a device which might even slightly infringe on a Trust patent was apt to result in an instant lawsuit against him. The Trust sought to control motion pictures from the beginning to the end, from production to exhibition.

New firms opposing the Patents Company, known as Independents, were an odd lot of producers, none of whom produced creditable films at the outset, if reviews are to be believed. Note In actuality, in 1910, when the first Thanhouser film was released, a truly unbiased review was hard to come by, for leading trade publications such as The New York Dramatic Mirror, The Film Index, The Moving Picture World, The Billboard, and others were fed by advertising revenues by the opposing Trust. However, it is apparent that many if not most films produced by the Independents were strictly amateur productions, while many of the products of Biograph, Kalem, and a few other members of the opposing Patents Company group had true entertainment and production merit.

Particularly notable for their content and production value, according to many film historians, were the films of Biograph, directed by D.W. Griffith from 1908 through 1913. In later years Griffith became famous, especially after the national acclaim given in 1915 to his monumental epic, The Birth of a Nation, produced in 1914, the year after he left Biograph. Note His Biograph pictures have been studied in detail by a later generation of scholars, a task simplified by the preservation of a large number of Biograph films and many of the company's records. Note

To circumvent the Patents Company firms and their aggressive lawyers and spies, Independent companies secured bootleg cameras if they could find them: otherwise, they had to be satisfied with newly-invented mechanisms, often of uncertain worth, or with cameras imported from Europe. Protecting their cameras from surveillance by unwanted curiosity seekers, the Independents in the early days engaged in film making at unannounced and private sites. The hills of Northern New Jersey and Southern Connecticut were favorite locations. Florida, Cuba, and the far West also furnished sites for Independent activities from time to time. However, most Independents were content to conduct business in New York City or Northern New Jersey, where they seem to have worked without gaining the attention of ruffians whom the Patents Company reportedly sent out from time to time. Lawsuits were another matter, and Thanhouser and other companies were harassed by them.

At the outset, the Independents garnered little press coverage. However, as the number of Independent firms and their advertising budgets grew, such companies as Carl Laemmle's Independent Moving Pictures Company of America (known by its initials, as Imp or IMP) Note, Yankee, Nestor, Powers, Champion, and others came in for their share of the limelight.

Although various Independent firms contributed financial and personnel resources to combating the Patents Company, it was Carl Laemmle who did the lion's share of the work. Week after week, trade papers printed his advertising cartoons deriding "General Flimco," a caricature of the Patents Company's releasing arm, the General Film Company. Finally, in 1915, the Patents Company lost a major suit brought against it under the Sherman Anti-Trust Act, and on October 1 of that year it was dissolved. However, the Patents lion had lost its teeth several years earlier, when various Independent companies found ways to secure needed equipment elsewhere. The General Film Company remained in business for several years thereafter, but on a diminished scale as one by one the original Patents Company members went out of business or discontinued motion picture production.

Eastman Kodak, whose raw film output was ostensibly controlled by the Patents Company by virtue of a signed exclusive contract, surreptitiously sold film through undisclosed agents to certain Independent manufacturers, who informed anyone who asked that the film stock was "imported." In 1911 the situation eased following a court decision which mandated that Eastman film was to be made available to Independent producers at a price equal to five percent above the rates charged to the Patents Company members. At the time, Eastman sold film in strips up to 400 feet in length.

Copyright © 1995 Q. David Bowers. All Rights Reserved.